Alaska oil and gas operators active on the North Slope face a long-term, existential threat to infrastructure for which there is no easy solution – thawing permafrost.

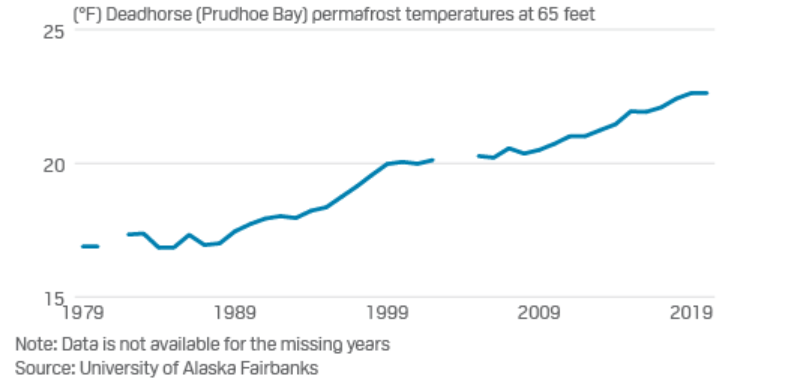

Scientists at the University of Alaska Fairbanks have been taking deep temperature measurements in permafrost soils underlying the producing oilfields on the slope and along the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System.

Since 1978, when measurements began, temperatures at the 65-foot depth have shown steady warming, with the steepest increase at 6 F in the oil fields at the northern end of TAPS.

In 1978 the permafrost at 65 feet near Prudhoe Bay was 16.3 F. By 2018 it had warmed to 22.6 F.

The warming hasn’t yet affected oil and gas production on the slope, and companies have strategies in place to deal with varying seasonal temperatures, including underground refrigeration units to keep the soil stable.

But the real impact may come from the effects of warming on surrounding infrastructure, including the critical Dalton Highway, the gravel road connecting the oil fields to interior Alaska.

From permafrost to slush

A new report by the university’s Geophysical Institute projects warming trends forward for the first time. The report forecasts that the melt point would be reached in 2100 at 65 feet.

The rate of change correlates with the rising atmospheric temperatures in the Arctic. The 65-foot depth was selected for measurement because this is deep enough to be unaffected by seasonal freeze-thaw cycles, said Santosh Panda, a scientist at UAF’s Geophysical Institute.

What’s important for industry is that the thaw point will be reached much earlier at shallower depths.

By 2050, many ice-rich silty soils underlying the North Slope will be at 32 F, essentially turning into silt slurry.

“It’s going to be a big mess at the top. I can’t even imagine what the landscape will look like,” he said.

ALASKA'S RISING PERMAFORST TEMPERATURES

Most of the North Slope is underlain by ice-rich silt that extends to bedrock. The depth of bedrock varies, but it’s deep in many places, said Doug Goering, dean of UAF’s College of Engineering and Mines.

“The mostly-organic material in the silt tends to collect water. There is a lot of ice in the first 20 to 30 feet of material that is particularly vulnerable to thaw,” he said.

If the thaw extends down 15-30 feet, the soils below surface infrastructure, like roads and airports, become unstable. “We’ll see road surfaces sink,” Goering said.

Subsidence from permafrost thaw hasn’t yet appeared in the oilfield areas, but state highway engineers are now on the front line of this battle on the Dalton Highway, a vital supply link.

Permafrost thaw is creating sinkholes and subsidence at one point 50 miles south of Prudhoe Bay.

“It’s a maintenance nightmare,” said Jeff Currey, materials engineer for the state Department of Transportation and Public Facilities.

Keeping the roadbed stable for trucks carrying oil field supplies is requiring constant laydown of new gravel

“It’s been about 20 to 30 truckloads so far this year, and that’s a lot for a small area,” of several hundred yards, Currey said.

“This is a short-term fix but it’s the best we can do for now.”

Trans Alaska Pipeline

The Trans Alaska Pipeline System is near the Dalton Highway and its operator, Alyeska Pipeline Service Co., hasn’t reported problems yet with Vertical Support Members, or VSMs, for the pipeline, which is built above-ground in the area because permafrost.

However, a small fuel gas line that supports TAPS operations became exposed a few years ago because of ice subsidence and erosion, according to reports. Alyeska placed rock to solve the immediate problem, but the filled area is now covered in water due to melting.

Natalie Lowman, spokesperson for ConocoPhillips, said her company has yet to see evidence of permafrost thaw that can be attributed to climate change. However, the company is sponsoring research at the University of Alaska Anchorage that includes permafrost.

In Interior Alaska the permafrost warming and thaw is more pronounced. Alyeska installed refrigeration systems at vertical supports in permafrost areas south of the Brooks Range when the pipeline was built in 1977. Those appear to be working well to keep soil stable in a radius around each VSM.

“You hire good engineers”

Producers’ trickiest problem isn’t so much the field well pads. Those can be elevated on thicker gravel and the technology of clustering wells and drilling extended horizontal wells is already well established. The challenge will be in protecting the high-value field processing plants and the TAPS system itself.

In the long term, North Slope fields may be developed, or redeveloped, more like offshore fields.

Go deeper: The technical challenges facing Alaska’s upstream developers

Harold Heinze, former ARCO Alaska President and also a former state natural resources commissioner, is more upbeat and feels doomsday predictions may be unwarranted.

Large process plants have been installed on piling and thick gravel pads with future permafrost impacts in mind, Heinze said. Many incorporate refrigeration systems to keep soils stable. However, roads and airfields may be at risk, he acknowledged.

Heinz believes industry has shown itself capable of dealing with permafrost over five decades and can rise to new challenges.

“Facility and pipeline design on the North Slope, including a gas line someday, all incorporate possible future permafrost situations,” he said.

“Current facilities have had minimal problems over the last fifty years because the assumptions of conditions have resulted in very robust designs that have neutralized potential problems,” Heinze said.

“People know how to build in specific permafrost situations and anticipating the condition 50 or 100 years from now is already on the table,” he said.

“It’s not a threat. It’s just another factor in going forward, and it’s why you hire good engineers.”