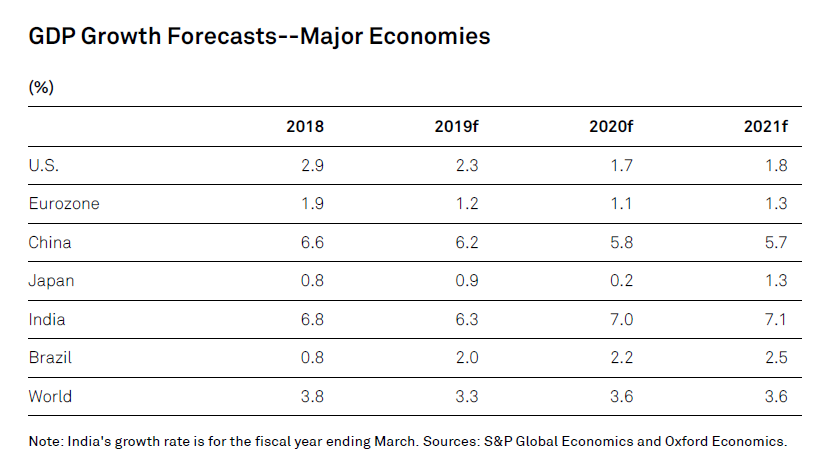

Oct. 01 2019 — Global economic growth continues to slow in an unsynchronized manner. The pattern of weak manufacturing and trade, offset by relatively strong household spending and labor markets, that began in late 2018 persisted into the third quarter of this year. The main driver of this slowdown is ongoing trade policy and technology uncertainties between the U.S. and China.

While the slowdown to date maps unevenly for individual countries, the turn in monetary policy this year has been almost universal. Nearly all central banks have loosened policy settings. The Federal Reserve cut rates twice in the third quarter, and the European Central Bank (ECB) pushed borrowing costs further into negative territory and restarted asset purchases. A slew of other central banks lowered rates as well. In contrast, we have seen much less action on fiscal policy.

Our baseline outlook is for a further moderation of growth into 2020, amid signs that the pace of manufacturing weakness is bottoming. Critically, household spending remains robust, and labor markets are tight. The lagged effects of monetary easing should provide support to activity in the coming quarters. Nevertheless, the downside risks are rising. Our main concern is that the impact of U.S.-China tensions spreads beyond manufacturing to the household sector, taking down global growth.

Global Growth Is Now Unsynchronized

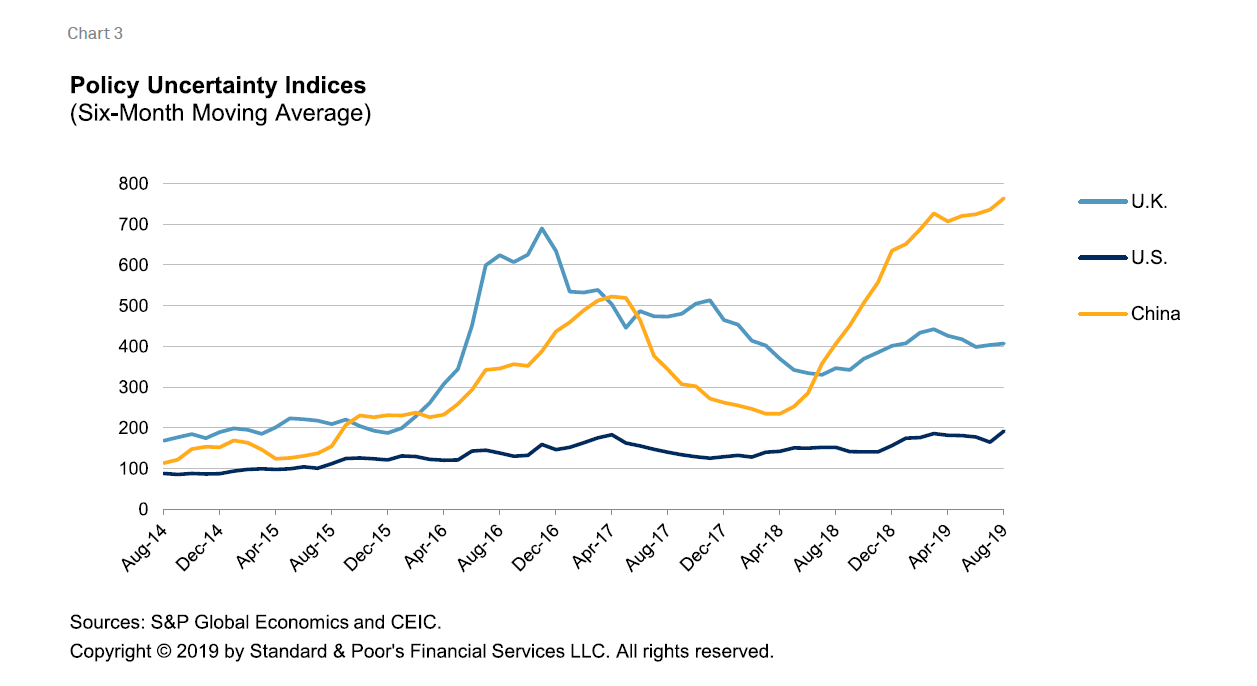

The synchronized global upturn of 2017-2018 now reads like ancient history. Overall, the macro picture is more worrisome than our scenario of a necessary and healthy slowdown envisaged earlier in the year (1). The main driver of the deterioration is uncertainties around the U.S.-China relationship. As the trade-tech war between the world's two largest economies drags on, business sentiment has weakened and companies have dialed back spending.

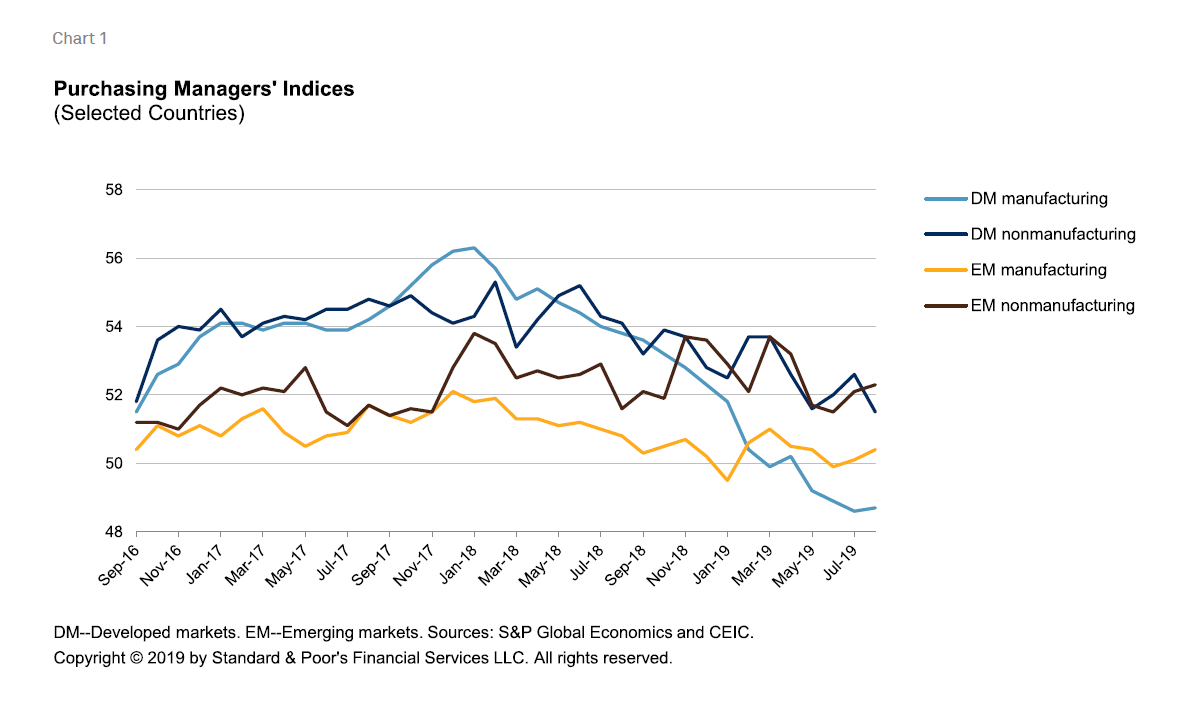

This deterioration can be seen clearly in purchasing managers' indices, or PMIs (see chart 1). While a general downtrend began last year, manufacturing sentiment in developed economies broke sharply lower late in the year, although there are now signs of a bottoming. The rift in emerging economies appeared earlier but has been less virulent, with the manufacturing reading remaining above 50 (2). Importantly, nonmanufacturing activity, a bigger driver of spending than manufacturing in most economies, has remained uniformly higher.

The differing impact of these uneven PMIs reflects differing compositions of growth across economies. To take some key examples, larger, less open, consumption-driven economies, such as the U.S. and China, are outperforming, since household spending on services is a relative driver of growth (3). In contrast, the more open, trade-led, manufacturing economies, such as Germany and South Korea, are struggling. Indeed, Germany appears on the cusp of a technical recession, since output fell marginally in the second quarter and looks weak in the third.

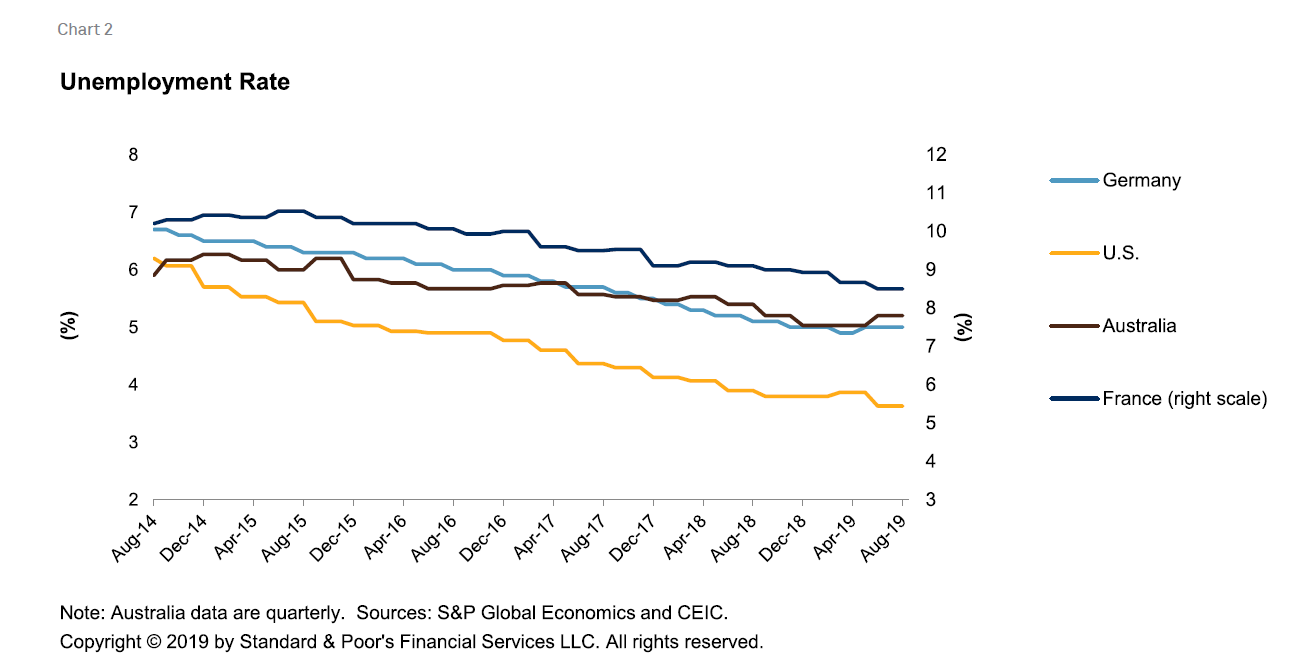

In contrast to cross-country differentiation in PMIs, labor market developments look uniform. This is underpinning consumer spending, which, again depending on the composition of the economy in question, drives at least part of the growth story. Unemployment trends are surprisingly synchronized given the variations in GDP growth (see chart 2). As we note below, continued strong labor market performance is a key component to our baseline forecast of moderate growth, rather than a sharper decline.

Monetary Policy: Still The Only Game In Town

With growth and (expected) inflation slowing, and downside risks to the outlook rising, the U-turn in monetary policy has been almost universal. Last year, the discussion was around the Fed's pace of policy-rate normalization (including its balance sheet), and the extent and pace to which other central banks would follow. This year, nearly all central banks have loosened policy settings. The Fed cut rates twice in the third quarter, and the ECB pushed borrowing costs further into negative territory and restarted asset purchases. Many other central banks lowered rates as well. We see two reasons for these moves:

Insurance cuts. These are preemptive and intended to forestall or minimize additional future cuts. The idea is to boost spending, growth, and inflation now and thereby preserve policy ammunition if needed later. This was the Fed's rationale for the rate cut in July, and it applies to central banks in countries where policy rates are approaching zero: Australia, New Zealand, and South Korea (all of which have been cutting rates).

We are unpersuaded by the argument that central banks should wait before cutting rates to preserve ammunition. The danger is that monetary authorities following this strategy will get behind the curve and need to do more, not less, to get growth and inflation back on track.

The stars are shifting (4). The equilibrium real interest rate "r-star" and the unemployment rate associated with full employment "u-star" have both moved lower. The reasons for this aren't yet fully understood but include a higher propensity to save at all interest rates, demographic factors (large saving among baby boomers), higher debt and the need to reduce leverage (or at least lower debt-to-income ratios), globalization pushing inflation lower, and increased uncertainty. Falling stars mean that real interest rates and unemployment can be lower than previously thought without stoking inflation. Hence, policy rates can be lower.

While the direction of macro policy has shifted toward accommodation in the past year, the mix of macro policy hasn't improved. Monetary policy appears to still be the only game in town in most cases, despite that a number of central banks are approaching the "zero bound." In the case of the ECB, while there is more ammunition, the effectiveness of monetary policy has reached its limits (5).

The reticence to use fiscal policy stems from a number of sources. In some cases, public debt levels are elevated, and modern monetary theory arguments that net debt is zero and fiscal policy should be used to ensure healthy growth and full employment seem to have gained little traction with policymakers. Political logjams are preventing fiscal-stimulus plans from being agreed on and executed in some countries. Alternatively, a perceived lack of suitable infrastructure projects argues against public spending in other countries.

Our Detailed View And Forecasts

Our current take on the major economies and regions are as follows:

U.S.

Growth in the U.S. has slowed but is still expanding at a rate close to its potential of around 2.0%. Second-quarter GDP growth was 2.0% on a seasonally adjusted, annualized basis, but was unbalanced. Consumption contributed more than 3 percentage points to this outcome, while investment, including a substantial inventory decline, subtracted more than 1 percentage point. A positive government spending impulse and weaker exports roughly canceled each other out. The Atlanta Fed's GDPNow measure (6) for the third quarter suggests that the overall pace of activity in the third quarter is broadly unchanged from the second-quarter pace, and the pattern of weak investment and strong consumption fueled by strong labor market data continues.

We forecast U.S. growth to remain slightly below 2% in 2020-2021, which, combined with an output gap near zero, puts the economy close to its steady-state path. However, our Business Cycle Barometer shows near-term recession risks are rising, and we now put the probability at 30%-35%--more than twice what it was a year ago (7).

The Fed met market expectations by delivering consecutive 25-basis-point cuts to the benchmark federal funds rate. These took place at its end of July and mid-September meetings. Statements following both policy meetings noted a strong labor market and consumer spending, and weak investment and external environments (8). We are forecasting one more quarter-point cut this year, with the Fed on hold through 2020.

Europe

Divergent economic outcomes in Europe reflect the divergent composition of growth this year. Germany, the EU's largest economy, appears close to a technical recession, with a contraction of 0.1% in the second quarter and expansion of just 0.5% year on year. In contrast, growth in France (0.4% in the second quarter, 1.3% year on year) and Spain (0.5%, 2.3%) looks more robust, featuring a high investment intensity, supported by strong labor markets. Italy continues to struggle with stagnation under the weight of low productivity and political instability. The U.K. economy also contracted, reflecting continued Brexit-related uncertainties, with growth trending around 1%--roughly half of its potential (9).

Like the Fed, the ECB eased its policy stance in the past quarter. At its September meeting, the ECB lowered the interest rate at its deposit facility 10 basis points, to -0.5%, and announced that it will restart its asset-buying program in November, with purchases of €20 billion per month, until it deems it necessary to raise the policy rate. It also announced a two-tier reserve remuneration system with some excess reserves exempt from the negative deposit rate.

Since the ECB has limited scope to lower its policy rate further, and the effects of quantitative easing on credit creation and the exchange rate appear limited, we see a strong case to raise fiscal spending in order to support demand and boost inflation. This is particularly true in countries with relatively low debt and negative government interest rates.

Overall, we see European growth slowing to 1.1% next year, from 1.2% this year, on the back of slower external demand. France and Spain will outperform while Germany will lag.

China

The pace of activity continues to slow--but growth appears to be 5%-6% on a sequential basis--reflecting declining trend growth, modest policy stimulus, and the negative effects of the trade war with the U.S. The weakness this year has been concentrated in slowing fixed-asset investment and sluggish exports. Consumption, the motor of Chinese growth, remains fairly robust. Activity in the important real estate sector remains firm, and policy intervention in this key sector has been absent.

In contrast to the Fed and the ECB, the People's Bank of China hasn't eased its monetary policy stance of late. Operations mainly are aimed at ensuring liquidity in the interbank market, which remains a major source of funding for smaller and more regionally focused banks.

Regarding the trade war, we estimate the short-term direct impact of U.S. tariffs on the economy to be manageable. The potential loss of price competitiveness stemming from U.S. import tariffs has been offset by an equivalent depreciation of the renminbi. In contrast, the loss of access to U.S. and Western chip technology would result in a much bigger, longer-lasting hit to Chinese growth through the productivity channel (10).

We expect GDP to expand 6.2% this year, in line with authorities' target of 6.0%-6.5%. There are some signals that the Chinese authorities could allow growth to slow below 6% next year, which would be a welcome development given years of credit-fueled investment (11).

Other major economies

In other major economies, the macro picture is weak on balance. Japanese growth is around 1% and trending lower as a result of negative trade developments. Growth in 2020 will take a hit from the consumption tax hike and decline to just 0.2%. Growth in India has declined more than expected, to 6.3%, owing to soft manufacturing and consumption. However, we expect a rebound toward potential growth of 7% next year helped by fiscal stimulus and corporate tax cuts.

The recovery of Brazil’s economy from a two-year recession remains sluggish amid external headwinds and domestic political uncertainties, but social security reform is improving sentiment. We expect a pickup in growth to 2% in 2020, from 0.8% this year (12).

U.S.-China Policy Uncertainty Drives The Downside To Our Global Outlook

Uncertainty around the U.S.-China relationship has led to lower growth, but the effects so far have been relatively concentrated and contained. The main risk to our baseline outlook is that these effects spread to the household sector, the main driver of growth in most economies. The trigger for this contagion is difficult to specify ex ante. One may simply be the duration of the conflict, another could be a rise in its intensity.

If the spat drags on, one possibility is that weak sentiment could migrate from the business sector to the consumer sector. In this narrative, consumer confidence could start to wane and household spending would fall. Firms would respond by cutting production to forestall rising inventories, and cut employment. This would hit household income growth and push consumption spending lower, starting the cycle downward.

The dispute could also intensify. This could include the extension of U.S. import tariffs to consumer goods (currently delayed), which would have a direct impact on consumer spending. Tariffs to date have mainly been on capital goods, and the effects have been spread out (13). Or it could involve an escalation of measures beyond tariffs. A direct hit to consumers' pocketbooks would likely generate not only lower real spending power, but also lower future spending through the confidence channel noted above.

In either case, consumer confidence and labor market developments will be key to distinguishing our baseline moderate growth forecast from a sharper decline.

From a macro-credit perspective, this "lower for longer" downside scenario shifts the risk from higher debt service (via higher market interest rates) to an earnings recession as consumer spending and corporate sales revenue decline. A full list of macro-credit downside risks can be found in our just completed quarterly credit conditions articles (see "Related Research").

For completeness, our upside risk scenario features a sharp reduction in uncertainty around the U.S.-China relationship that would unlock deferred investment and boost confidence and growth (14). This requires clarity of intent from both sides and some give-and-take leading to agreement and a reset of the relationship. This scenario carries a low probability since mistrust is currently high and both sides have dug in.

However, the outlines of a solution are clear. China, the rising power, wants to continue on its development path with its own model. The existing powers want a rules-based order with continued access to the vast Chinese market. Recognition of the other side's concerns is key. China may have to give up its insistence on being treated as a developing country, and credibly step up ongoing verification and enforcement around intellectual property. The West may have to allow China to enter technology and other sensitive sectors, as long as the rules are followed, and avoid wholesale bans that the Chinese perceive as containment.

A Global Economy With Some Fight Left

To borrow a boxing analogy, the global macro story is down but not out. Growth has slowed, but the damage so far has been contained to manufacturing. This isn't without pain, and things could clearly get worse. Developments in the household sector, which has largely been spared so far, will be key. Consumer sentiment and labor markets are the areas to watch.

The main, but not only, headwind to growth is U.S.-China relations. These negotiations are difficult but not insurmountable. Both sides will have to give a bit, and the solution won't be some one-off magical deal. There will be areas where the two sides will agree to disagree, and monitoring of any agreement will need to be ongoing.

The stakes around the discussions are high. Meaningful progress and a reduction in tensions will help not only those two economies but everyone else. From the global macro perspective, progress and agreement could be the difference between extending the long (but modestly paced) post-crisis expansion and entering a recession that was eminently avoidable.